See also: Specific Dance Histories

See also: Specific Dance Histories

Women’s Lib came a lot earlier to Scotland than most of us realise, while the fair sex in England were still doing their embroidery and meekly honouring and obeying, a major bastion in Scotland was crumbling.

It was late in the 19th century when a young woman called Jenny Douglas struck the first decisive blow for sexual equality and competed in a Highland Dancing Competition.

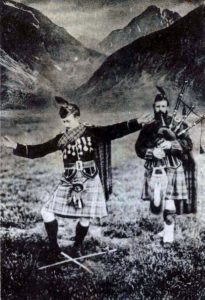

When organised Highland Games were instituted with caber-tossing, hammer throwing, and piping the dancing contests too, were male events.

No-one had ever considered that girls could dance or wish to compete, but Jenny entered and was accepted on the principle that which was not forbidden must be permitted.

By 1900 that first girlish drop had become a substantial trickle and then a flood so that today the position is reversed and the girls outnumber the boys by roughly 100 to 1. August and September are the traditional months for many of the big games and it can be seen that those taking part in the dancing are nearly all girls, the boys sticking out like a sore thumb with a tammy on top.

Highland Dancing is entirely different from Scottish Country Dancing, which by its nature, is a group dance form in which sets of 2,3,4 or 5 couples perform the steps and figures together. Highland Dancing, on the other hand, is essentially solo dancing, no partners being involved. Two Country Dances are however classified as Highland Dances for the purpose of competition – The Reel of Tulloch and The Argyll Broadswords.

The real Highland Dances, of which there are only three, – The Highland Fling, the Sword Dance, and the Seann Triubhas – were most definitely not a lassies game in their original form. Of the three, the Fling is the oldest. It is considered to be based on the rutting movements of the stag, a kind of fertility dance. All the movements, the arms held aloft like antlers, the feet dancing from side to side and the body turning round suggests the stag. The date of its origin is not known for certain but it was probably being danced by Highland men before Christianity came to Scotland. It is also said that the Highland Fling was later used to show agility and strength among the military. Being danced on a shield, often with a spike at the center, it was imperative the dancer be steady and stable throughout the dance’s duration.

Malcolm Canmore, King of the Scots, is accredited with the Sword Dance. The story goes that in 1058 he slew his opponent and, overjoyed at his victory, placed his own sword and that of his enemy on the ground in the form of a cross and danced in triumph over them.

The wearing of the kilt, or rather the ban on its wearing, brings us to the third of the trio of Highland Dances – the Seann Triubhas. This is the youngest of the Highland Dances having been devised during the period after Culloden when the wearing of the kilt was forbidden, often under the penalty of death. The name Seann Triubhas, loosely translated from the Gaelic, means ugly or unwanted trousers, and the movements of the dance, the shake, shake, down of the leg, are visible attempts to discard the hated garment. Many men dance it in tartan trews for greater effect.

None of these three dances were ever intended to be danced by women and one can imagine the shock when Jenny Douglas stepped on to the boards and opened the floodgates of women’s participation.

The period between the two World Wars saw the growth in popularity of Highland Dancing as a pastime, and it was a poor town, or village, that didn’t boast a Teacher of Dancing.

Girl pupils wore exactly the same dress as the boys – bonnet, velvet jacket, jabot, plaid, kilt, sporran and hose. Some girls even wore the sgiain dubh for everyone took it for granted that Highland dress meant the lot.

In competitions judging was often a case of bias in favour of a particular style used in some part of the country and even if a dancer’s performance was absolutely correct, if it was not the style the judge preferred, the dancer was in danger of being marked down as a result.

The system of selecting judges left a lot to be desired; the adjudicator very often being just a well known dancer, with that as the only recommendation to justify his fee. Rules, where they existed, could vary depending on in which contest the dancer wished to compete, although it must be said that the major gatherings laid down quite firm guidelines.

Cowal Highland Gathering, amongst others, made its conditions quite plain in their programme of events, under the heading “Rules for Dancers” were included:

- Birth Certificates must be produced on demand.

- No judge will be allowed to judge more than one event in Scottish Championships.

- All protests must be in writing accompanied by a deposit of £1.

- Don’t wear medals on your doublet, or any jewellery other than Highland Dress ornaments.

- Don’t chew gum when dancing.

- Don’t glance at the judges when dancing.

These rules were right and proper but there existed no governing body which could formulate a consistent procedure covering all Highland Dancing contests. Medal-hungry dancers became easy prey to so-called organisers who arranged local competitions in halls and rooms up and down the country, and there is no doubt that a great deal of fiddling besides piping went on at these venues.

All local contests at this time were not rigged, but a great number were suspect. Dancers in one age group of, say 10 to 12 years old, could find themselves competing in an entry of 60 to 70 children with only three medals awarded. Distressing scenes could occur at the end of the day, with angry mums besieging the judges.

Meanwhile great strides had been taken to ensure the pipe band contests were judged fairly. Adjudicators sat within closed tents relying only on their hearing to select the best. Similar considerations could not be accorded to dancers until in 1950 interested parties got together to devise how to arrive at an overall policy that would ensure that standards were the same in all teaching and contests, dress and judging. After months of research and discussion the Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing (S.O.B.H.D.) was formed.

All the steps in the dances were standardised, as was the order in which the steps should be performed – eight steps for the Fling, six slow and two quick for the Sword Dance, and eight slow and six quick for the Seann Triubhas. A book was published which included judging standards, and finally dress for the dancers. A form of kilt dress for females was devised and out went the head-dresses, plaids, sporrans and belts and in came a fitted and boned velvet waistcoat with short-sleeved blouse along with the Kilt. The official board dress also put paid to the widely-used custom of schools of dancing dressing all their pupils on one particular tartan and style. It was like handing a visiting card to an adjudicator and intimidating the lone competitor.

National Dances became part of the contest scene in the 1960s and with their introduction formed a very attractive element in addition to the Highland Dances. The National Dances mainly for girls had seldom been seen. The dances themselves are old but they brought a whole new dimension to the scene, being danced in an up-to-date version of he old Aboyne Dress for girls. This consisted of a laced velvet waistcoat, ruffled blouse, belted plaid, full tartan skirt over petticoats, and either long white stockings or bare legs. It’s a dress that lends itself perfectly to the dances as in most movements the skirt is held in the fingers. Seven of the National Dances are now permissible at most contests.

The Seven National Dances selected by the board – all solo – are:

- The Scottish Lilt

- Flora Macdonald’s Fancy

- The Earl of Errol

- Highland Laddie

- Blue Bonnets over the Border

- The Village Maid; and lastly

- Wilt Thou Go to the Barracks Johnnie.

In 2020 the name was changed to the Royal Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing. The R.S.O.B.H.D. is now affiliated to the Scottish Pipe Band Association who are responsible for the organisation of Bands in Games and contests. There are very few competitions today which are not staged under R.S.O.B.H.D. rules.

Highland Dancers can now tread the boards, take exams via medal tests which give an unbiased assessment of their ability, and compete in an unprejudiced and competitive atmosphere giving pleasure to the thousands who watch.